Read the full article below!!!

Or

Download and save/print this article:

PITCHING MECHANICS

Don’t Overcoach!!

To put it bluntly, verbal mechanical cues are making kids bad at throwing. For example, the commonly shouted phrase “Use your legs more!” does not even begin to scratch the surface in terms of teaching a kid how to implement the lower half of his body in a throwing motion. Most of them instinctively respond by pushing harder and later. After all, this is what they do in almost every other basic athletic movement (jump, run, squat, etc.). In reality, this does nothing but lock up their core muscles (in an attempt to maintain some sort of balance and body control) which, in turn, makes it impossible to create separation between their hips and shoulders; an absolutely essential part of creating velocity while lowering stress on the elbow and shoulder.

And let’s also make a pact to stop telling our kids to “throw strikes.” He is probably struggling with his confidence at this point if he’s having trouble with his control. Do we really think that explaining to him one of the most basic concepts of the game is going to do anything other than make him feel even worse? Honestly, I see this as a comment made to make ourselves, as coaches, feel like we are doing something to help because we don’t know what else to do. Instead, tell him to “keep attacking the zone” or to “be aggressive.” I can guarantee that he is trying to throw strikes. But, if he puts pressure on himself to do so, he will square up to home plate too soon in his delivery. This will put undue strain on his arm and indeed have the exact opposite effect of throwing the ball more precisely.

These are just a couple small examples of how a well-intentioned verbal cue can mislead our players. And, unfortunately, there seem to be thousands of these cues that have been passed down from generation to generation with no scientific merit. I know because I was “taught” just about all of them. What we are learning from higher level technology (high speed cameras, motus sleeves, etc.) is that a lot of what we once thought was happening in the throwing motion, isn’t correct. Further, most players have no ability to mimic what they see or what somebody is telling them to do. Attempting to create a movement pattern that is not natural to their bodies creates stress (physical AND mental), reduces performance and limits improvement. They are becoming robotic. So, what should we do?

Intent is the key word. The reason long toss has been around for so many years is because it forces a very simple intent…throw the ball as far as possible. And every individual’s body knows (or naturally learns) how best to do this. Ideally, every player could go back and start their throwing careers from scratch. Having no idea how to throw a ball, the player would be able to create his most effective throwing motion through the self-teaching of long toss.

I’ve had the opportunity to play in several foreign countries and one thing always stuck out to me. The young kids had incredible throwing movements and skills, yet it was apparent that none of them had any sort of coaching or instruction. It either didn’t exist or was financially impossible. I see this as an advantage in the scope of this particular discussion.

We are past that point with our players. Instead, we need to create ways to make the throwing motion NOT feel like what they are used to. This creates an environment in which the player’s body must start to make corrections naturally to achieve the desired result. One of the most effective ways to create this new environment is by changing the weight of the object being thrown. Another is to implement a drill that forces the desired action. These methods give the player the ability to FEEL the change, which is essential to the process. One of the drills we use to force front leg stability, balance, and energy transfer is to simply have the players play catch while standing only on their glove side foot.

…back to intent. Mechanics are developed via an attempt to throw hard IN PRACTICE!! If your pitcher is on the mound struggling, there is no on-the-spot mechanical change he can make to suddenly turn everything around. What most of these players need is confidence, reassurance, positive motivation. Explain to them that you don’t care about whatever bad results have occurred up to that point. All you want is for him to stay aggressive and competitive…to never give up. After all, a year from now nobody will remember any of this. So instead of dwelling on what the next result might be, he needs to simply focus on the intent of his next fastball. Throw it hard and challenge the hitter.

Actual Mechanics

The main goal of the rest of this article is to focus on some of the main mechanical and conceptual flaws that I see in this area of the country and to address corrective drills for each of them. I LOVE talking about how pitchers’ (all athletes really) bodies move, so any questions/discussions are highly encouraged!! Please feel free to reach out to me.

Back Leg vs. Front Leg – This is one of the most common misconceptions I come across when teaching pitching. Most believe that power (hitting and pitching) is mainly derived from the back leg, which is probably why it has been given the title “drive leg.” Research shows, however, that there is no direct correlation between back leg usage effort and velocity. On the other hand, there IS data proving that if a player can efficiently transfer energy from the front leg into and through the upper body, then they will increase velocity and power. The previously mentioned balance drill is a great way to teach this feel. Stand on the glove side leg facing your throwing partner. Turn shoulders and fire. Follow through with arm and upper body as normal, but do not lose balance from the front leg. This should be used at long distances or with velocity from shorter lengths. It’s surprising to most to discover just how far a ball can be thrown without the use of the “drive” leg.

Glove Arm Usage – The glove arm should be used aggressively early in the upper body portion of the throw. When done correctly, it will transfer energy into the throwing arm adding velocity while reducing the amount of throwing arm effort. The specifics of this movement can change from pitcher to pitcher. One key is that we are trying to create a powerful angle with our shoulders (usually uphill) and working to spread out our chest. When performed early enough, the glove should automatically find itself somewhere around the ribcage/chest area at the time of ball release.

A great drill for this is the knee drill. Player faces throwing partner while kneeling on both knees. Turn shoulders and throw. Long throws from this position are the key. It forces the thrower to use his glove arm and create angles similar to what is shown in the pictures above.

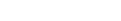

Arm Slot – Myth…you will get injured throwing sidearm.

As you can see, two hall-of-fame level pitchers (Scherzer and Pedro - very different body types) use(d) a sidearm delivery to dominate hitters. And I can’t remember either of them having any sort of arm issues. For the most part, the body dictates what the arm slot should be. More specifically, the angle at which the shoulders rotate should deliver the arm and hand through that same angle in order to maximize energy efficiency (lower stress, higher velocity). When we freeze big league pitchers at their release point, we see a common theme…there is a straight line from the glove side shoulder, through the throwing shoulder, to the throwing hand. Here are a couple of additional still photos of guys with different arm angles. Take note of how the shoulder tilt coincides with (determines) the arm slot.

Without getting too technical, there is a sweet spot when it comes to throwing elbow positioning in relation to the throwing shoulder. If the elbow gets too high (in relation to the shoulder joint) on the back side, it tends to create an impingement in the shoulder and can lead to injury (like the labrum tear I suffered). If the elbow stays too low (again, in relation to the shoulder joint) it tends to cause strain in the elbow or forearm. So, we should not try to force a particular arm slot onto our pitchers. The way their bodies want to create rotation will deliver the arm naturally. A good drill to find out what works most naturally is the knee drill. It focuses on the upper body involvement in the throw. At long distances the body will tend to do what it knows it must do to get the ball to that distance. We can both teach the player and learn about them during this drill.

Final Thought

I cannot emphasize enough that the way a player throws is all about feel. He may think his body is doing one thing (feel), but in fact be doing something completely different. So, if we tell him to get his arm to a certain point (we may be right in what we are asking), he will try and even feel like he is doing what we asked. The actual result, however, will probably be off. My suggestion is to work to find ways to create feel for a pitcher who needs to assess a mechanical deficiency. And as I said earlier, I am pretty much always available to help with this!

Tag(s): Home